In 2021, a total of 851 civilians and public officials in Malaysia were arrested for corruption, as per statista.com. This indicates a slight decrease in arrests related to corruption in a country with a slightly above average score in terms of the Corruption Perception Index, though Malaysia can be credited with implementing measures to tackle corruption and bribery.

Combating corruption has gradually been rising to the top of policymakers’ and company agendas. Even though it has long been a prevalent issue, there is a greater awareness today of the negative implications of corruption on both the social and economic development fronts.

How to tackle corruption cases in Malaysia?

Cases such as the Sabah Water Department, 1MDB, Port Klang Free Zone (PKFZ) and Immigration Department Scandal in the last five years illustrate how corruption and bribery are deeply embedded within Malaysia’s political and Government institutions. Statistics suggest that the increasing number of agencies that aim to combat corruption are running into a dead wall. However, adopting newly devised measures such as corporate liability for corruption offences coming into effect in Malaysia could be a turning point for tackling corruption and bribery.

Corruption is regarded as a complex, multifaceted phenomenon. Nevertheless, it is widely defined as the abuse of public power and violation of rules for private gains. Whilst there is a perception that it is carried out primarily by government officials, corruption can occur across various sectors and be executed by those other than government officials.

Corruption cases in Malaysia include bribery, extortion, fraud, embezzlement, blackmail, illegal gambling, laundering and nepotism, all of which encompass the abuse and misuse of public power and authority. This includes public officials taking or offering bribes through money or service, which is dishonest. Subsequently, it is often the abuse of trusted power for personal gain. It is considered a consequence of poor governance and undermines the state’s legitimacy.

The impact of corruption cases in Malaysia

Corruption has social, political and economic impacts, which arises through the distortion of law and weakening of institutional foundation on which economic growth depends. Furthermore, it threatens democracy, contributes to the unjust distribution of income and burdens taxpayers. On a wider national level, it undermines free and fair trade. Although corruption has negative implications wherever it is present, the impact on developing nations is often heightened.

Corruption reduces the economic resources available to address social, economic, and political issues that may hinder development. This issue impacts society the greatest by impeding economic growth, government expenditure, and investment. It is a greater detriment to the poor, worsening income inequality and poverty. From a business perspective, it additionally reduces the efficiency of firms and increases the costs of business.

Combating corruption and promoting integrity has become a key aim within Malaysia due to how corruption has occurred and its evident impact on the social, political and economic landscape. It is estimated that corruption may cost up to RM10 billion a year within Malaysia, equivalent to 2.3 billion $USD. It is estimated that this accounts for up to 2% of Malaysia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The Asian financial crisis has acted as a catalyst for combating corruption, shifting public perception of corrupt practices and, in turn, bringing it to the forefront of public policy.

What the statistics say

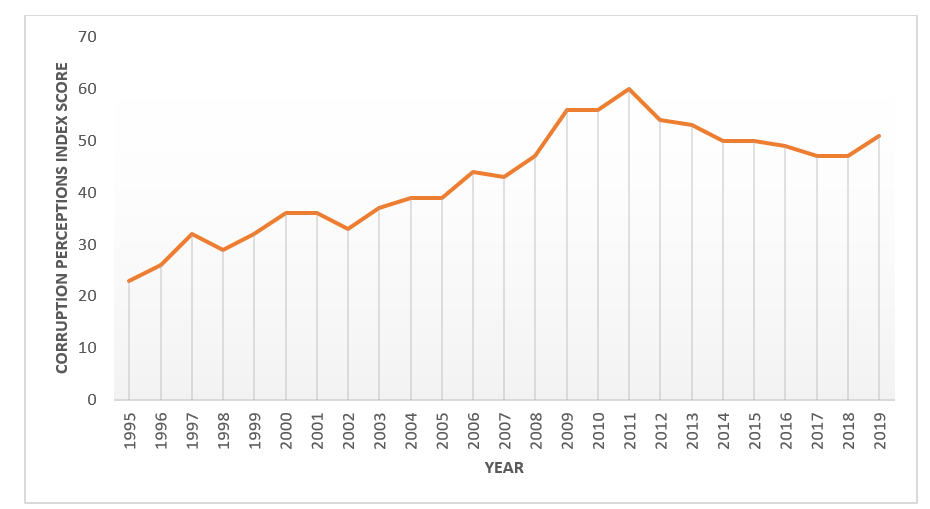

Malaysia is the 62 least corrupt nation out of 180 countries, according to the 2021 Corruption Perceptions Index reported by Transparency International.

Data suggests that efforts to combat corruption in Malaysia have been futile. This includes over 66% of the public believing that there has been no improvement to the transparency and integrity levels within the public and private sectors. In addition, in 2007, 47% of corporate managers revealed that they had been involved in bribery within the past 12 months or knew someone who had been involved with bribery within the past 12 months. The highest levels of corruption were found within the police, followed by other enforcement agencies such as customs departments and roads and transport.

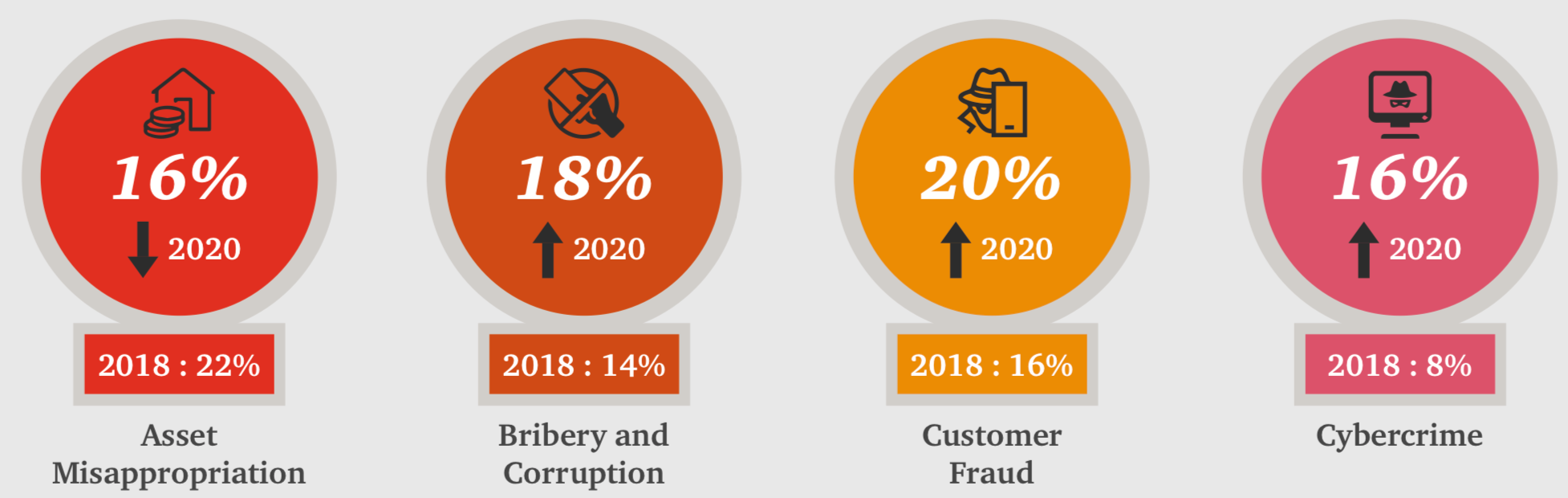

In 2020, according to Pricewaterhouse Coopers (PWC), the four most disruptive forms of fraud experienced in Malaysian organisations were asset misappropriation, bribery and corruption, customer fraud and cybercrime (see table below). These account for 70% of all economic crimes in Malaysia.

The four most disruptive forms of fraud in Malaysia in 2020.

In addition, public procurement is considered a key sector in Malaysia in which corruption is high. In such instances, Malaysian companies are favoured over foreign competitors due to political connections.

Addressing corruption

The previously highlighted impacts of corruption have encouraged an extensive list of measures to tackle corruption within Malaysia, as seen in Table 1. The Malaysian Government has acknowledged the harmful nature of corruption to economic growth. It has led to many bodies being given the responsibility to address corruption and have implemented many steps to ensure its minimisation and eventual eradication. Combating corruption promotes integrity within society.

Efforts to combat corruption within Malaysia began with the Anti-Corruption Agency set up in 1967. This included the Malaysian Administrative Modernisation and Management Planning Unit, the anti-corruption Agency, the Auditors General Office, the Public Accounts Committee, and the Public Complains Bureau. Early successes included the prosecution of several political leaders and senior civil servants.

Nevertheless, corruption remained high. Research has, however, found that these institutions are ineffective at combatting corruption through continued cases of unlawful transactions and misconduct. However, since 2003, corruption has been high on the agenda of government strategies, with 2003 marking the admittance of Prime Minister Abdullah Ahman Badawi, who declared that fighting corruption would be a key and prime priority. This led to several new initiatives, including the National Integrity Plan in 2005, which aims to promote a culture of integrity.

This was followed by the Malaysian Institute of Integrity (MII), which supports and coordinates and implements the NIP. More recently, the governmental Transformational Program has been introduced to enhance the effectiveness of combating corruption. This includes the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC), which began operation in 2009, reporting to a Parliamentary Special Committee on Corruption.

Two of the early agencies aimed to table corruption.

| Name | Date of establishment | Aim | Powers |

| Anti Corruption Agency (ACA) | 1967 | Preventing and eradicating all forms of corruption, misuse of power | Investigate, interrogate, address and prosecute offenders. Access documents and witnesses, freeze assets, seize passports. Minor income and assets |

| Public Complaints Bureau | 1990 | Addresses alleged administrative lapses and abuse in dealing with public bureaucracy. | Receives and investigates complaints from public dissatisfaction with government administration |

Cases of corruption and bribery

There has been a high level of corruption cases in Malaysia – ongoing for decades despite increasing efforts to combat these issues. A number of these cases will be explored, establishing the levels of corruption they entailed and how they were investigated and came to light.

The case of the 1MDB (2015)

One of the most prominent corruption cases in Malaysia involves the former Prime Minister of Malaysia, Najib Razak, known as the 1 Malaysia Development Fund Bhd (1MDB). This corruption case involved the embezzlement of billions of US dollars facilitated by the false declaration by officials. The 1MDB was set up in 2009, initially launched at the Terengganu Investment Authority (TIA). It developed as a network of joint ventures between Aarbar Investments PJSC and Petro Saudi International. It is estimated that more than US$ 6.5 billion flowed through the 1MDB, financing the spending of corrupt officials and their associates.

In addition to embezzlement and bribery, money laundering was a component of the 1MDB scandal, which involved receiving and retaining money from sources and disguising or failing to investigate its origins. This violated the anti-money laundering laws within Malaysia, with banks acting as intermediaries and beneficiaries, which is in breach of their anti-money laundering compliance requirements. In addition, false declaration and bond mispricing between 2009 and 2014 were forms of corruption within this scandal, including the false declaration of 1MDB funds to banks in Malaysia. Recipients of these false declarations included Bank Negara (Malaysian Central Bank).

Investigations of the 1MDB scandal in 2015 highlighted several reasons why such an extensive corruption and bribery case occurred. It was found that governance systems in place were defective, leading to weak control over spending, lending and investment within 1MDB. This includes decisions made outside the board of directors and the board being fed false and inaccurate information, confirming that the Companies Act of 1965 of the Malaysian Code of Corporate Governance was not in compliance.

Since Najib was both Prime Minister and Chairman of the 1MDB Advisory Board, there was a strong lack of political will as there was no one above him to address the corruption. Political control further crushed attempts to deal with the corruption, which included removing the Attorney General from office and the harassment of the MACC officers. In addition, within Malaysian banks, and evidently internationally, there were weak internal rules against money laundering, which enabled such money flows.

As a result of the scandal, there were two key fallouts:

- The Malaysian Government were forced to pay US$1.66 billion to debt servicing payments; and

- There was significant erosion of trust within the public, particularly politicians and government officials.

The case of the Sabah Water Department (2010)

Before the previous case, the largest corruption scandal in Malaysia was considered to be the Sabah State Water Corruption scandal. This case involved the siphoning of RM3.3B worth of federal allocations for state rural water projects from 2010 onwards to top department officials. This is the equivalent of over 759 million $USD. The case arose due to complaints that water development project contracts were being distributed unfairly.

The two suspects who were investigated included the Director of the Water Department and the Deputy Director. It is estimated that these two civil servants amassed a sum of almost RM115 million (24 million $USD) due to their illicit activities. Such sums of money amassed due to the water department officials abusing their power to award contracts to 38 companies owned by their families or corrupt business officials.

As a result, an investigation was carried out by the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC), who subsequently confiscated cash, luxury cars, jewellery and watches amounting to RM 114.5M. Before the previous 1MDM corruption case, it was considered the largest amount of money confiscated by the MACC. Investigations revealed that many factors led to ongoing corruption taking place. This included the lack of systematic monitoring procedures which otherwise should have been in place to vet projects and irregular transactions. As a result, it led to the misappropriation of public funds, resulting in a weakened trust by the public of governance.

The case of the Port Klang Free Zone (PKFZ) (2007)

The Port Klang Free Zone (PKFZ) was a free trade zone at Malaysia largest port. Implemented in 2008, the project was designed to act as a hub for businesses to connect from over 120 countries due to its logistical location, which allowed for efficient business transactions.

A corruption case arose regarding Port Klang when it became evident that there were cost overruns of RM 3.5 billion, almost double the initial costs of RM 1.845 billion. There were reports that the Transport Minister at the time, Chan Kong Choy, had issued support for bonds which amounted to RM 3.7 billion without the Government’s approval. Pricewaterhouse Coopers was asked to conduct an audit to investigate the financial irregularities.

However, the audit found that the total cost amounted to RM 12.5 billion (almost 3 billion $USD), far higher than the initially suspected discrepancies. After these findings, an investigation was carried out by the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) and the police, leading to many people being charged with misconduct, including involvement with administering and financing the PKFZ. Even though the MACC was successful in carrying out an investigation, it has been widely dubbed as the scandal with no culprit, undermining the efforts and effectiveness of the institution in tackling corruption.

The immigration department migrant scandal (2016)

This scandal occurred in 2016, involving the Malaysian Immigration Department, which is considered to have been part of long-standing small-scale corruption such as bribery. An internal probe revealed several forms of corruption, including the tampering of the online system within the immigration department, which allowed for the access of cash and the movement of individuals who were not in line with immigration rules.

This was a form of corruption, but it also aided in terrorist activities, as it is suggested that over 130 Malaysians were thought to have travelled to Syria and Iraq to fight with ISIS as a result of misconduct. It led to many arrests and charges for human trafficking and allowed the illegal movement of migrants in and out of the country.

The fallout of corruption cases in Malaysia

Although it is clear that there has been extensive effort to tackle corruption cases in Malaysia, it remains a significant issue with significant economic and social repercussions. The level of corruption has remained high, questioning the effectiveness of strategies in combating corruption. This includes the effectiveness of MACC, which aims to investigate corruption at higher levels. However, the fact that it is subservient to the Prime Minister’s department limits its capacity as a way in which to prosecute high profile corruption cases.

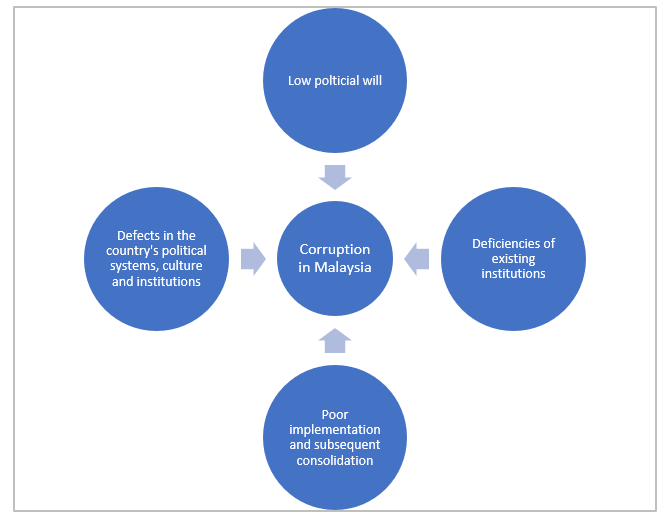

It is additionally key to highlight why corruption cases in Malaysia are rampant. Many factors have undermined anti-corruption policies, including failing to tackle political corruption and defects in Malaysia’s political systems, culture, and institutions. Further reasoning of the ineffectiveness of government initiatives that aim to tackle corruption includes low public support towards government efforts, the inability to address the root cause of this issue and reluctance and duplications (see table below).

Factors that affect Malaysia’s ability to tackle corruption.

In addition, greater corruption prevention strategies should be implemented. This includes corporate social responsibility practices, wherein a company’s risk of bribery and corruption should be assessed and mitigated within the overall approach to corporate social responsibility. This will ensure that corruption cases in Malaysia are tackled from within the government, rather than focusing on external ways to track and investigate corruption.

However, the MACC Act 2009 has introduced a new amendment, including within section 17A, which aims to enhance how corruption is tackled by adopting new penalties. The introduction of corporate liability for corruption offences has come into effect in June 2020, which essentially means that if there are any forms of corruption within a business, those involved in the management of its affairs, be it officers, partners, or directors, could be personally liable for the same offence. The only way to avoid liability is to exercise due diligence known as ‘Adequate Procedures’, which commercial organisations in Malaysia are expected to implement by 1 June 2020. Non-compliance is severe, resulting in penalties of RM1 million (230,000 $USD) and up to 20 years imprisonment.

The way forward

Because corruption cases in Malaysia are rooted in economic and political conditions, it is complex, making remedial efforts difficult. The significant impacts of corruption highlighted, including impeding economic growth, increasing income inequality and leading to poor trust in Government and political institutions, make it clear that eradication would benefit Malaysia’s economic, social and political landscape. This includes enhancing per capita income growth, leading to a greater flow of foreign investment and enhanced business growth.

Although widespread efforts have already been made through various old and new anti-government agencies and policies, these measures should continue to be enforced and adapted to minimise corruption cases in Malaysia in the future.

Demonstrating “Adequate Procedures” through ISO 37001 Certification

In complying with these guidelines and proving “adequate procedures,” public and private sector organisations should strongly consider the ISO 37001 certification process, which would provide proper assurance that the organisation has succeeded in establishing, implementing, maintaining, reviewing and improving its Anti-Bribery Management System.

ISO 37001 Anti-Bribery Management System is an internationally accepted standard that specifies the procedures an organisation should implement to prevent bribery while detecting and reporting any bribery incident.

The standard requires organisations to implement these procedures on a reasonable and proportionate basis according to the type and size of the organisation and the nature and extent of bribery risks faced. It applies to small, medium and large organisations in the public and private sector and can be implemented in any country. Though it will not guarantee that bribery will completely cease, the standard can help establish that the organisation has reasonable, proportionate and adequate anti-bribery procedures in place.

Author

Zafar I. Anjum, MSc, MS, LLM, CFE, CII, CIS, Int. Dip. (Fin. Crime), MICA, MIPI, MAB

Group Chief Executive Officer

(Certified Fraud Examiner)

(Certified International Investigator)

(MSc Counter Fraud and Counter Corruption Studies, University of Portsmouth UK)

(Master of Fraud and Financial Crime – CSU Australia)

LL.M Legal Practice (Intellectual Property)

t: +44 7588 454959 | e: zanjum@CRIgroup.com | LinkedIn

Building 30 years’ career in anti-corruption, compliance, risk management, fraud prevention, protective integrity, security and compliance, Zafar Anjum is a highly respected professional in his field. As a trusted authority in anti-bribery and anti-corruption, fraud risk assessment and prevention, corporate compliance evaluation, securities among corporate clients, government agencies and industry groups, he is known for creating stable and secure networks across challenging global markets. With an impressive educational background and his industry expertise, Zafar Anjum is often the first certified global investigator when multi-national EMEA corporations seek to close compliance, anti-bribery and anti-corruption or corporate security gaps.

Starting his educational background in 1989 with his Bachelor of Arts Degree; he then went on to earn a Master of Science in Counter Fraud and Counter Corruption University of Portsmouth in the United Kingdom along with specialised knowledge and certification in Fraud Investigations, Fraud and Financial Crimes, Corporate Fraud Control and Anti-Corruption. He was also awarded Distinction in Master of Fraud and Financial Crime and was included in the Executive Dean’s List of 2016 by Charles Sturt University, Australia.

All while continuing to earn his LL.M Legal Practice (Master of Laws) (Intellectual Property) from the University of Law in the United Kingdom, which he completed in February 2019. While enhancing further capabilities and competencies, specifically in the Bribery Risk Assessment framework, he is undertaking ICA International Diploma in Governance Risk, and Compliance, ICA International Diploma in Financial Crime and Prevention, ICA International Diploma in Anti Money Laundering from International Compliance Training Academy in the United Kingdom which is mapped and are also awarded in association with Alliance Manchester Business School, The University of Manchester.

His training and business acumen gives Zafar Anjum in-depth precision when dealing with fraud risk management, security consultations, crime investigations, crisis management, risk governance, event security and strategic threat management for industry leaders seeking proactive long-term risk prevention.

His leadership abilities create strong collaborative relationships among prevention teams, crime investigators, government officials, and business executives seeking dynamic solutions across international marketplaces.

For industries needing large project management, safeguard testing and real-time compliance applications, Zafar Anjum is the assurance expert of choice for industry professionals.

We’re here to serve you, Let’s Talk!

[…] here to read the full […]